Photos: Chris Emeott

Two locals share how they celebrate the Day of the Dead.

It’s late October in Querétaro, Mexico, and the streets are a riot of color. Overhead, panels of intricately cut tissue paper flutter in the wind. Vendors line the downtown streets with carts offering sugary confections—sugar skulls with frosting trim, candied pumpkins, brioche-like buns. And everywhere, the scent of orange cempasúchil flowers fills the air.

This is the Day of the Dead as Plymouth local and owner of La Cocina de Ana, Ana Rayas, remembers it in her hometown. “Growing up with that is just a beautiful thing,” Rayas says. “It’s not a sad remembrance. You try to remember the good and the fun and what [the dead] liked.”

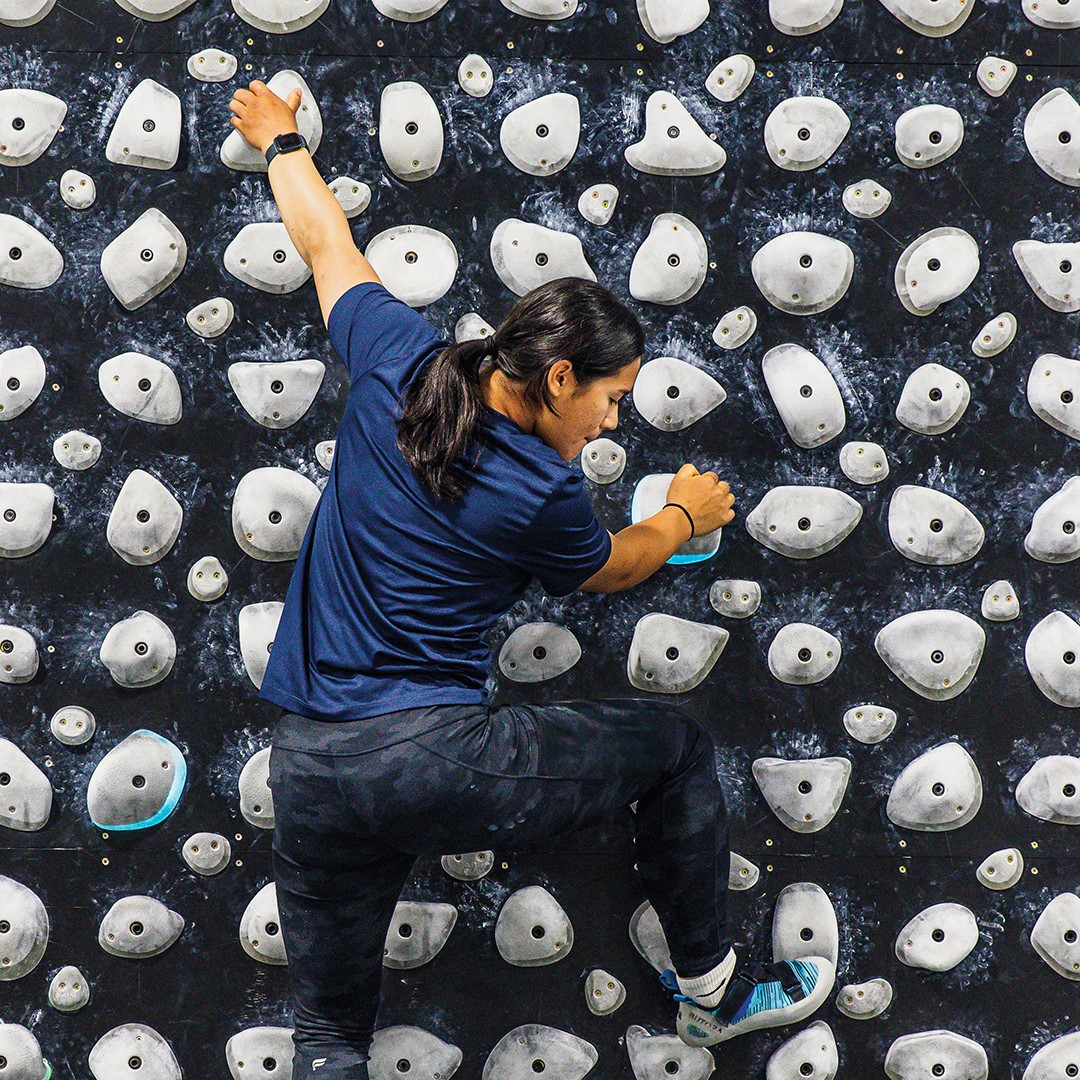

Ana Raya at La Cocina de Ana

Día de los Muertos comes from the combination of native Mexican traditions with the Catholic celebration of All Saints’ Day. Generally celebrated on November 1 and 2, the holiday represents a time of communication between the living and the dead, when souls are called back to their families to once again partake in the joys of life.

Rayas says that the holiday is one of the biggest in Mexico. “Everywhere it is celebrated, just in different ways,” she says. Large cities might put out public altars to celebrate the departed. Families might cook the favorite dishes of the dead. In some smaller towns, some cemeteries still come alive with activity, laughter and lights.

In her household, Rayas says her daughter—born on November 2—tends to take charge. “She’s the one that’s like, ‘Oh, let’s start the altar de muertos,’” Rayas says.

Altars are as unique as the families that create them, but there are some common elements, like photographs of the departed. “Ours is a smaller altar in my kitchen,” Rayas says. “They can be as complicated or as simple as you want.”

For Ana’s friend and Maple Grove resident Judith Díaz, her altar plays a prominent role in celebrating Día de los Muertos from October 27 to November 3.

Usually, Díaz constructs an altar on a side table in remembrance of her husband’s father and her family’s beloved husky. This year will be different. “This year is very important because my dad passed away in December, so I want to do a special altar this year,” Rayas says. Her plan is to take over the dining room table. “Of course in my parents house, my sister is going to decorate the whole first floor,” she says.

Díaz’s Día de los Muertos traditions are informed by her childhood in southern Mexico. “In my dad’s town, I remember that we used to celebrate in the cemetery the whole night,” Díaz says. “They put the ofrenda (altar) on the tomb, and then they have music. And you were having a good time also with the neighbors, because the tombs are close to each other, so you were celebrating together.”

Calaveras, or sugar skulls, Rayas purchased on a recent trip to Mexico.

Anatomy of an Altar

Díaz says that every element of the altar has symbolic meaning. For her three-level altar, she includes the following items:

Water: “You need to have water, clean water, and you need to change it every day,” Díaz says. “It’s an element of purification.”

Salt: Díaz also places a small container of salt on her altar. “The salt represents the purification of the soul,” she says.

Bread: Pan de muerto is a rich, brioche-like bread baked specifically for Día de los Muertos. “That represents the body, the physical world,” Díaz says.

Flowers: The bright orange marigold, or cempasúchil, features heavily in the celebrations. “Usually, that represents the perfection of life,” she says.

Petals: “You also have a lot of petals that you put on the floor,” Diaz says. “They are guiding your loved ones that are coming to visit you to the altar.”

Candles: Díaz uses different colored candles as decoration, but she says that white candles are what she traditionally lights each night in celebration of different souls coming to visit.

Incense: The woody copal is the type of Mexican incense specifically associated with Día de los Muertos.

Día de los Muertos altar created by Ana Rayas.

Who’s Coming to Visit?

In Judith Díaz’s tradition, each day focuses on a different set of spiritual visitors.

October 27: Pets

October 28: Souls without a family

October 29: People who didn’t have hope when they died

October 30: Souls that passed away via an accident

October 31: Family ancestors

November 1 (All Saints’ Day): Young children “It’s when you put all the food in the altar,” Díaz says.

November 2: Adults from your immediate family

November 3: On the last day, Díaz says goodbye to the visiting souls and asks them to come back next year.

Pan de Muerto

As part of her family’s celebration, Rayas bakes the iconic Día de los Muertos treat. “It’s a very moist, eggy, not very sweet, buttery bread. On top, what they do is interesting. You have to know about it because when you see it, it’s hard to tell, but it’s bones, like a femur. They make those shapes and put them on top of the bread,” she says.

Pan de Muerto with the traditional dough “bones” creating an X design on top.

Rayas says that each year, La Cocina de Ana is inundated with calls for pan de muerto. Currently, she only makes it for her family. “It’s so much work,” Rayas says. “Maybe one of these days, if I have a helper, I’ll make it.”

La Cocina de Ana

15725 37th Ave. N. Suite 4; 763.432.9181

Facebook: La Cocina de Ana – Plymouth Vicksburg

Instagram: @_la_cocina_de_ana_